Automobiles were big business in Little Rock by 1918, and theft was quite the problem. Nearly every day, the Arkansas Gazette or Arkansas Democrat reported another mistake by neglected children or nefarious larceny by shadowy syndicate sorts.

One hundred years ago today, the Gazette briefed readers on one tool for fighting back: A Pulaski County deputy sheriff, W.F. "Will" Sibeck, had ducked into the Palace theater for a break after a frustrating day spent failing to locate a 1918 Chandler stolen from Dr. E.C. Walt. As the reporter described it, Sibeck parked his own Ford outside while he watched movie detectives trailing lost girls by clinging to the rim of the extra tire mounted on the backsides of Ford taxis.

When the show was over, he went to the shadows, where he had left his car. Quell the palps, dear reader, he found the Ford. But not without marks of violence on its otherwise imperturbed enamel.

Unlike an "ordinary Ford," which could be started by anyone willing to run the risk of turning its crank and thus was like a tramp dog ready to follow the first stranger that patted its head, Sibeck's auto was equipped with a "self-starter." Invented by Charles Kettering about 1912, this was an electronic ignition switch installed inside the automobile body, and it required a key.

Sibeck found a strange key in the switch, and three screws off the switch plate lay on the floorboard. The Gazette remarked that the would-be thieves failed "because there is only one key to every self-starter, somewhat in the manner of a Yale lock."

I've read that Ford didn't offer self-starters until 1919. Did Sibeck rig one up for himself? Did the reporter have the make wrong? I have no idea.

By the way, those old cranks were seriously dangerous. They broke thumbs, noses and jaws, dislocated shoulders, knocked people out. Hence our word "cranky."

Traffic violations and terrible wrecks were rampant, too, especially on the road to Camp Pike, where thousands of soldiers were training to join the war in Europe. On March 5, 1918, the Little Rock Railway & Electric Co.'s public notice in the Gazette announced that North Little Rock had bought a motorcycle. It would be put into service "with a policeman in the saddle whose special duty it will be to get after speed maniacs."

I was surprised to read in the notice that "the motorcycle cop" would be able to see speeders in time to give chase. Was "cop" not considered insulting to police in 1918? In his online entry on "cop," Evan Morris, aka "The Word Detective," notes that during his 1950s childhood it was as disrespectful as swearing (look up his item in the index at word-detective.com). But the slang has a long history of semi-respectability; I've seen it in the Gazette as early as 1874.

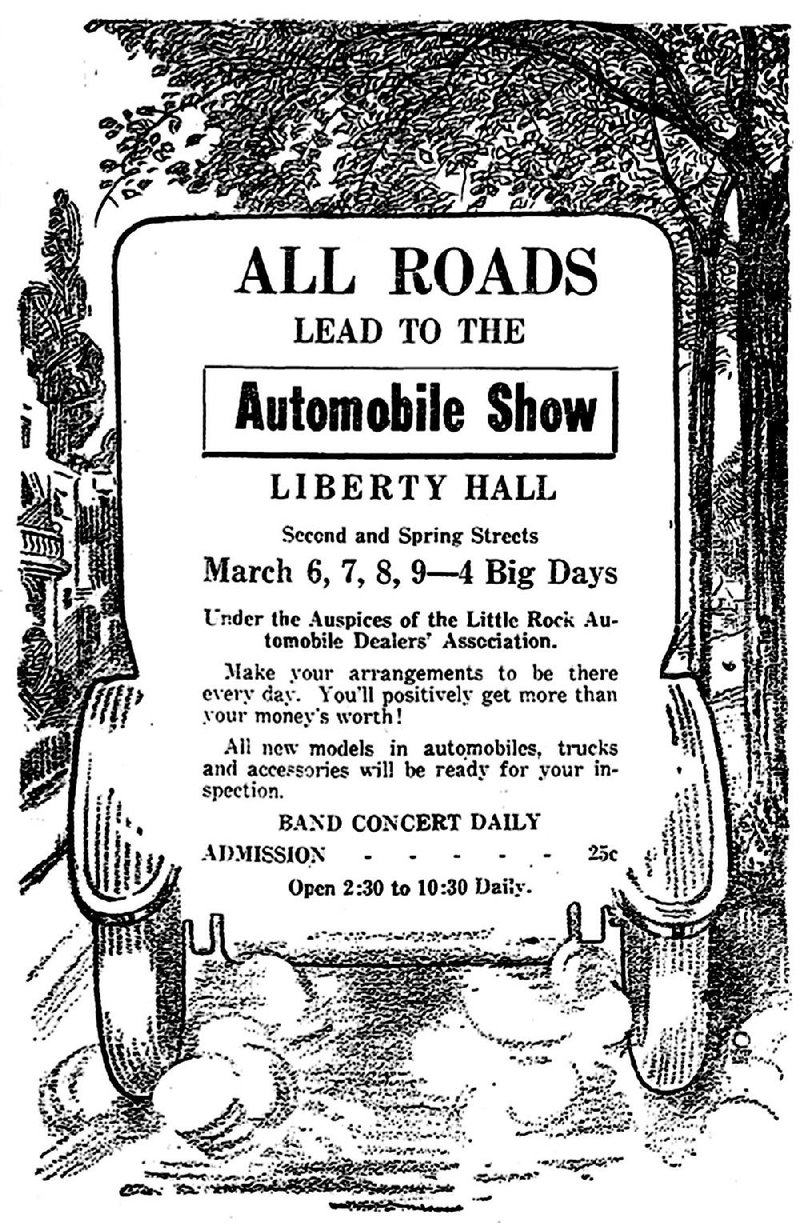

All that to say this -- 100 years ago this week, the Little Rock Automobile Dealers' Association held its first auto show in Arkansas.

New York's sensational National Automobile Show began in 1900; Chicago and Boston had them, and they generated news around the country. In 1911, the fact that some buddies planned to motor from Helena to Memphis for a giant auto show was news here.

Little Rock dealerships staged small shows at state and county fairs. In 1914, the Little Rock Motor Club organized an automobiles day at the Arkansas State Fair in Hot Springs. It celebrated the start of work on the $30,000 Little Rock-Hot Springs Highway (U.S. 70). In 1916, the Pulaski County Fair included a parade and a show, with 26 makes of autos displayed in the dancing pavilion at Forest Park.

The big to-do in 1918 was organized hastily, in less than a month. Open from 2:30 to 10:30 p.m. March 6-9, Wednesday through Saturday, it included musical performances, food -- but mostly it alerted citizens to the existence of the 30 dealerships in Little Rock.

Trucks as well as 43 models of passenger cars were crammed into the largest available space, Liberty Hall. Thanks to Bernadette Cahill's book Arkansas Women and the Right to Vote (Butler Center Books, 2015), I can tell you that Liberty Hall was a large building on the southwest corner of Second and Spring streets, a site once called "Donkey Hill."

That's a well packed parking lot today. In 1918, the building was packed so full that vehicles were displayed in waves. Applications for booth space from 15 dealers were turned down. Refusing to be denied, two dealers from Pine Bluff and Fort Smith erected a tent behind the hall.

Women's organizations sold sandwiches and coffee; reps came from out of state to hawk tires, spark plugs and accessories; even the Little Rock Police had a booth, where they explained that larceny did not pay.

A detail of police and firemen were on hand with 12 fire extinguishers.

The Democrat reported 2,500 to 3,000 visitors the first day and twice as many on the last. Gov. Charles Brough told the opening-day crowd there were 40,000 automobiles in the state. He predicted Arkansas would spend $15 million to upgrade roads in the next five years.

Little Rock Motor Car Co. made the first sale one minute after the doors opened: W.H. Hagood of Tyro bought a Saxon roadster.

While the Gazette covered the show like white on rice, the Democrat had to be content with basic reports and big cartoons in the middle of its front page. This art bears the signature of a cartoonist for the Evansville Courier in Evansville, Ind., K.K. Knecht. Democrat editorials had extolled the genius of Karl Kae Knecht over the years. He was a warrior for free speech. But it appears these auto-show cartoons were reprints rather than done-for-hire (but I could be wrong).

The Democrat stood on the sidelines while the Gazette took in the lion's share of automobile ads, quite possibly because ad manager H.K. Seymour was in on the first planning session. Consequently, for March 3, his press ran the largest edition it ever had printed in one night -- 76 eight-column pages, including a 32-page automotive section. This tome was delivered to 58,610 subscribers.

A story in the March 4 Gazette estimated the weight of all that newsprint at 39 tons, which is what you get by multiplying 120 rolls of paper by 650 pounds apiece. It also equated that tonnage to the weight of 1 1/3 cars -- which looks to modern eyes like what you get by mishandling a decimal point. And that might be what happened; but in 1918, the automobile was still for the most part "the automobile." "Cars" tended to be train cars.

By coincidence, I feel sure, on March 11 a terrible auto accident occupied the center of the Democrat's front page, under a three-column photograph of the trashed seven-passenger Studebaker. Six people were badly hurt. Miss Audrey Pugh of Little Rock died.

Email:

ActiveStyle on 03/05/2018