HARDY COUNTY, W.Va. — Carved out of the wilderness around where the Lost River disappears to flow underground in West Virginia is a stronghold built for survival. It doubles as a bed-and-breakfast.

It’s called Fortitude Ranch, and right now Drew Miller’s survival community has some 100 members ready to take cover on the 64-acre property that backs up to the 18,000-acre George Washington National Forest.

To the uninitiated, the ranch is an Appalachian bed-and-breakfast billed as a prime weekend destination. Guests are asked to take off their shoes in the main house, are served fresh eggs from the free-range chickens for breakfast and are treated to clean beds.

But for members, most of whom don’t live on the ranch, this place in the foothills of the Shenandoah Mountains will serve as shelter should a cataclysmic event impact the Earth.

“We’re prepared for any kind of collapse. You name it, we think we could get through it,” said Mr. Miller, whose dissertation for his Harvard University doctorate in operations research was on underground nuclear defense shelters.

Mr. Miller’s work as an intelligence officer and former Air Force colonel involved creating strategic catastrophic scenarios similar to the ones he has prepared for in this camp. He said a pandemic could kill 90 percent of the population, and that is the type of event Fortitude Ranch is most prepared to face.

Tom, a member who would give only his first name for the purposes of this article, said the doomsday scenarios that worry him most are, in order, “pandemic, solar flare or civil war.”

Tom is from Maryland, some three hours away. “If I thought my life would be in danger, then I’m heading here,” he said.

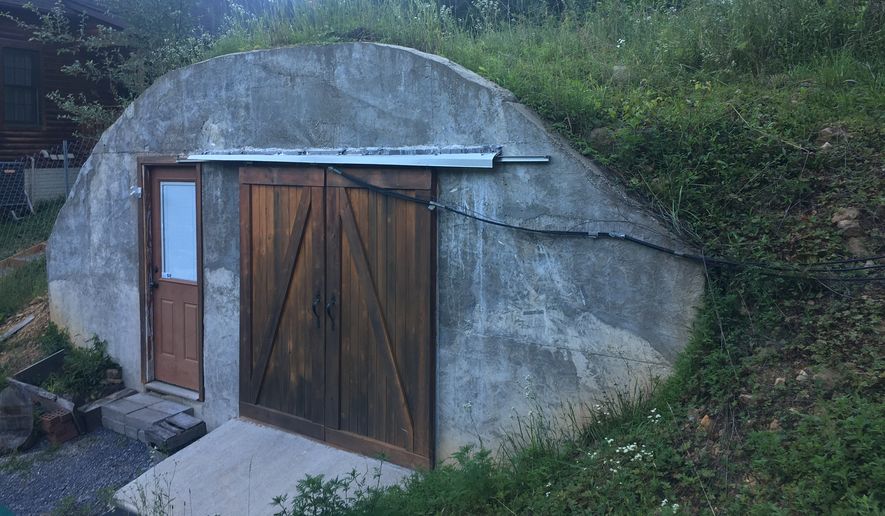

Nearly everything on Fortitude Ranch serves a dual purpose.

“In good times, this is a gazebo,” said Mr. Miller, showing off a thick log structure that looks very much like a gazebo. “A 50 cal will go right through this, but most other bullets, this will stop them.”

“We’ve done high English teas out here,” said Mr. Miller, “but the main reason I built this is that this is a guard’s station — and a good one.”

He calls the decks that overhang the walls of the log cabin fallout shelter he is building “bastions” and recounts that “a lot of our technology is from castles.” The multistory treehouse on the other side of a patch of trees would act as a guard station in a time of crisis.

“It’s a fun place to be in good times, but it’s also a defensive position for our guards,” said Mr. Miller. “You’re up higher, plus you can shoot over the wall.”

It sometimes takes imagination to zero in on the full scope of Mr. Miller’s vision.

Fortitude Ranch is building a second outpost in Colorado, and 10 more compounds are planned to open in remote areas across the country to create a nationwide network. If members are away from home and unable to reach their “base ranch,” then they are free to take shelter at the closest site.

Walking through the depths of a solar-powered, 7,000-square-foot complex that will serve as a dual-use shelter and lodge, Mr. Miller showed off a dozen or so square chambers along the 120-foot-long basement. The tar-covered reinforced steel ceiling, which will be covered with 3 feet of earth, is meant to protect members from radioactive fallout.

Mr. Miller’s contingency plan for these rooms in a pandemic situation can be unnerving. Each cell will have its own air supply. In the event of a pandemic, Mr. Miller said, members will come out of their rooms in shifts to prevent exposure to infection.

Asked if that scenario would presuppose a certain amount of trust in Mr. Miller, he said, “Well, in our staff.”

One of those staff members is Zach Mikolashek, a volunteer firefighter and Marine Corps veteran of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Most members have basic gun-handling skills, but Mr. Mikolashek shows guests how to “blast away with whatever you want” — including AR-15 assault-style rifles, 12-gauge shotguns, handguns and sniper rifles — on the remote firing range. Members store guns, ammunition, valuables and supplies in individual lockers on site.

“Most of them are professionals,” Mr. Miller said of his members.

Subscribers pay some $1,000 a year in dues and are “people who work full time, and they don’t really have time for this and they’ve done the math and it’s a lot cheaper to join us than to try to do this on your own. I mean orders of magnitude cheaper,” he said.

The spartan accommodations on Fortitude Ranch are a selling point.

“That’s why we can do $1,000 a year: because it isn’t fancy,” said Mr. Miller. The idea is that middle-class Americans could buy into this system and they could survive an end-of-the-world situation for a sustainable amount of time. The more people who buy into Fortitude Ranch, “the cheaper it gets,” said Mr. Miller.

The motto: “Prepare for the worst, enjoy the present.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.