Operation Kudu: Ukrainian soldiers training in the UK

A clear day in March in the south of England. The sun's rays barely break through the trees in the dense forest.

"Radio check, over." The sound of the Ukrainian language reaches us through the English woodland.

A dashing man in military uniform, weighed down with ammunition, an assault rifle over his shoulder, is checking the connection with his comrades.

"Roger, over," his comrade says over the radio.

"Where are the maps, Lionia?" another Ukrainian fighter asks in a loud voice.

"Everything’s in place," Lionia replies.

"Let’s go," the senior member of the group orders.

And with that, the Ukrainian soldiers start their combat training in the forest. Their task: to destroy the positions of an imaginary enemy beyond the marsh.

"It’s been my lifelong dream to come to the UK to walk through swamps," one of the soldiers jokes with the UP journalists. "I don't remember walking through swamps like this one at home in Kherson Oblast. English forests are nothing like Ukrainian ones in this respect."

The Ukrainians’ training is being overseen by foreign instructors. Before starting their practical field training, the soldiers study theory according to the Interflex programme for Ukrainian soldiers, which is based on British Army standards.

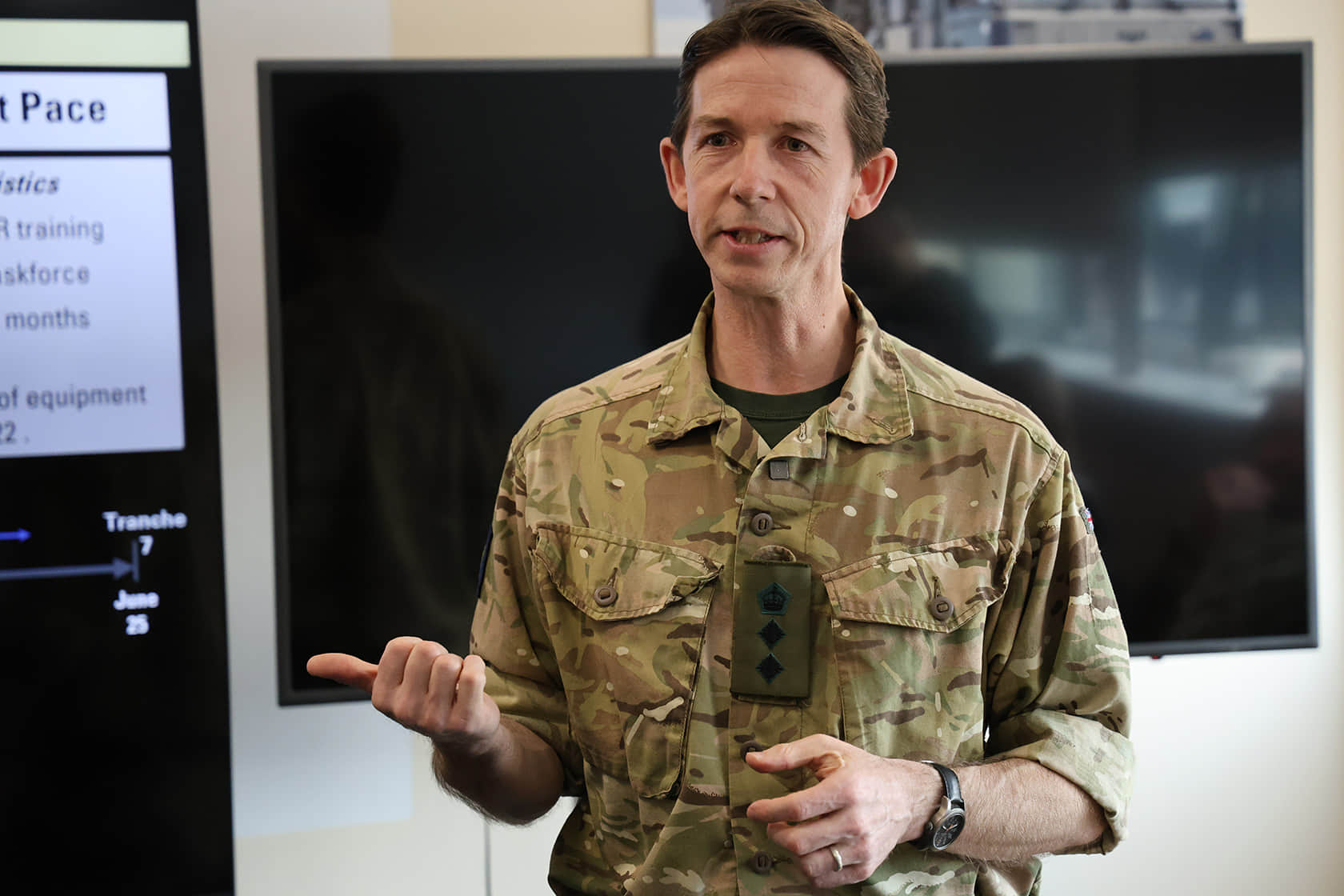

Over the past two and a half years, the UK has trained more than 52,000 members of the Ukrainian defence forces to fight in the war against Russia. Less than 1% of them went absent without leave (AWOL) during training, says Colonel Andy Boardman, Commander of Operation Interflex.

A high-ranking source in the Ukrainian military told Ukrainska Pravda that only two soldiers went AWOL in the UK in 2024, and 12 others have done so since the beginning of 2025.

Interflex has three key areas: basic training for new recruits, instructor training, and leadership courses for junior officers. 60% of those enrolled in the programme in Ukraine are new recruits, 30% are officers and 10% are instructors, Colonel Boardman says.

Ukrainska Pravda visited a base and training grounds where new Ukrainian recruits are turned into crack troops, soldiers become instructors, and experienced officers hone their skills. Read our report to find out how it happens.

The airfield, the "market", all inclusive

Our journey begins at N Airfield in Poland, where the Ukrainian soldiers are about to set off for their training in the UK.

Several hundred soldiers in civvies are lined up in front of the airport with huge bags. One by one, they are called for a pre-flight check.

The servicemen look tired, but their eyes show a keen interest in everything going on around them. For many of them, this is the first time they have been abroad since the full-scale war started, and for some it’s the first time in their lives.

Most of them are officers who are also psychologists, and they are travelling abroad to develop their skills.

The huge aircraft takes off to the sound of applause on board. This is strange because in peacetime, it’s after landing that Ukrainian passengers usually clap, even though the pilots won't hear them.

The following morning we catch up with the soldiers at the Interflex Distribution and Sorting Centre in a provincial region of England, where they are being kitted out from head to toe.

At the entrance to the long warehouse, we’re greeted by a board full of notices like "Looking for a husband", "Contraband cigarettes", "Dugout building". Ukrainian soldiers who visit the hub write their aliases and hometowns on it – "Suleiman from Chernihiv", "Baton (Loaf) from Kamianske", "Kharakternyk from Kyiv" – as well as patriotic slogans and messages to their successors.

"Stand on the cardboard and try on your trousers, quick!" A commanding female voice rings out from the other end of the huge warehouse, distracting us from our tour of the centre.

A dozen burly men politely follow the order and change into their military uniforms while standing on a piece of cardboard, for all the world as if they were trying on clothes or shoes in a Ukrainian street market.

The interpreter later jokes to UP that at Interflex, she feels like she is at a bazaar.

Before they are sent to the base, the centre provides the "cadets" with everything they need - from uniforms, footwear, body armour and helmets to personal hygiene products and tourniquets. Thirteen countries are helping the UK to kit the soldiers out. The Ukrainians take all the items provided by the host country home after completing the course.

The soldiers are fed at the distribution centre in a self-service canteen format. There’s a wide choice of dishes for both meat-eaters and vegetarians. The soldiers are offered several different side dishes, meat and fish, salads, steamed and raw vegetables, fruit, yoghurt, coffee, tea and juices.

From the outside, the room resembles an ordinary Ukrainian canteen, except that there are no drawings on the walls, which are popular in our provincial towns.

After lunch, kitted out and well fed, the soldiers set off for training at the Interflex base.

"Got your things? Shall we head out?" one soldier asks his comrade hesitantly before leaving the hub.

"Affirmative! Bags packed and off we go," his comrade jokes as if they were off on a combat mission.

Shooting, drones, assaults

The Ukrainian soldiers at the Interflex base wake up at six in the morning. They have breakfast. They collect their weapons – described as "a British version of the Kalashnikov" – and make their way to the firing range. We go along with them.

The road to the training ground winds through several provincial towns in the south of England. Here and there, horses graze by the roadside, wrapped in what look like coats – rain covers to shield them from the damp. Foggy Albion (as Ukrainians sometimes call the UK) is a trend-setter. Unlike in Ukraine, the only thing that falls from the sky in England is rain. So the soldiers can train in peace without the distraction of air-raid warnings.

The course for new recruits lasts seven weeks. The British Army unit commander in charge of training at Interflex tells us that the Ukrainians are trained not only by instructors with theoretical knowledge, but also by specialists with combat experience in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Although the commander has never been to Ukraine himself, he monitors the situation on the Russo-Ukrainian front daily through reports from Operation Interflex headquarters and news reports, as well as by talking with the "cadets".

Today the soldiers are firing at static targets from various distances, lying down and standing, with single charges and in bursts. The process is overseen by foreign military personnel. Every word they say, whether it's a command, criticism or praise, is translated for the Ukrainian recruits by interpreters.

Olha, one of the interpreters, told UP that nearly 70% of the Ukrainians who come for training in the UK do not speak English. She has been working at Interflex for almost two years.

Olha’s working day is 11 hours long. All that time she is with the soldiers and their instructor: she translates lectures and formal and informal conversations, runs obstacle courses, goes on reconnaissance missions, and shoots.

"The first Ukrainian words that the foreign instructors learn are usually swear words. Sometimes they are very effective. When a British company officer ends a briefing with the question: "Zaiebis?" (Kapish?), asking whether everything is clear, the guys answer: "Yes, zaiebis!" It boosts morale and brings people closer together," Olha smiles.

The instructors tell everyone who has finished shooting at the range that next time they will have a training session on firing at moving targets on the move.

"We can fire as many rounds as we need to. In Ukraine almost all the rounds are sent to the front line, but the UK doesn’t have that problem," a burly man in MultiCam and a balaclava tells UP. He’s a senior lieutenant who goes by the alias Vorskla, being a fan of the Vorskla Poltava football club.

Vorskla served as a professional soldier in the Armed Forces of Ukraine until 2005, when he was promoted to officer. He returned to the army as a mobilised soldier in December 2024 and initially underwent basic general military training in Ukraine. After internal selection in one of the assault brigades, he was sent to the UK for training.

"Our instructors are learning alongside the new recruits," says the commander of Interflex, Colonel Andy Boardman. "We have our tactics and training techniques, and the Armed Forces of Ukraine have theirs. We put them together. We integrate the Ukrainian experience into our course for new recruits."

One of the innovations that the British have made to their programme based on the Ukrainians' experience is drone training. The instructors teach the soldiers how to evade threats of surveillance and direct attacks from drones.

"We place huge emphasis on drone use in any tactical operations carried out by the Ukrainian trainees on our course. To do this, we work very closely with Ukrainian instructors who are drone operators to recreate the tactics and techniques that they use on the front line," the commander of the British Army unit responsible for training at Interflex tells UP.

We move from the firing range to the forest, where the Ukrainian soldiers are practising combat tactics in groups.

Nearby is a huge field where a flock of "elite" English sheep is grazing. Why are they elite? Because if any soldier accidentally shoots a sheep, the owner must be paid many times its value.

The surrounding landscape and the natural obstacles that the soldiers have to overcome while performing their training tasks to some extent resemble the north of Ukraine.

Each group is assigned different tasks. One group sets up an ambush, another goes on reconnaissance, and the third must destroy enemy positions or evacuate wounded soldiers.

First the soldiers plan the operation in detail and allocate duties and functions. The instructors do not interfere at this stage, but allow the Ukrainians to make their own choices about the events unfolding.

The soldiers then head out to perform their tasks. At this stage the instructors do get involved and correct the Ukrainian soldiers’ actions during the process.

A few of the instructors stand out from the rest. Their faces are hidden behind balaclavas, and they wear a patch marked "Operation Kudu" that has a trident embroidered in the centre, flanked by a kangaroo and an emu.

It turns out that some of the Ukrainian soldiers are being trained by instructors from the Australian army.

"Why is there that name on the patch? Is it an Australian name?" the journalists ask.

"No. I don't even know why it's called that. Probably so that no one will figure it out," the Australian instructor answers, smiling.

In fact, the kudu is a species of antelope found in Eastern and Southern Africa that has no connection to either Britain or Australia.

"The Australians taking part in Operation Kudu teach leadership courses for commanders and sergeants," the instructor tells UP. "We try to instil leadership principles in the Ukrainians. Our focus is on first aid and tactical combat care under fire, survival skills and offensive spirit."

We can hear shots being fired from various directions and shouts of:

"Smoke! Where's the f**king smoke? Drop it!"

"We gotta evacuate the wounded!"

"Fire!"

The mock battle ends. Time for a debriefing.

"Look, here you made the right choice, but you could have moved a little faster. And here you should have sent reconnaissance," the instructor explains to the Ukrainians.

It is notable that there is no hint of scolding or bossiness in the conversation. Everything is conveyed calmly, but in a voice of military clarity.

After completing several tasks, the soldiers go back to base.

It’s morning. Boarding is almost complete on a military aircraft, which takes off from an undisclosed airbase in the south of England.

"Glory to Ukraine!" rings out from the loudspeaker.

"Glory to the heroes!" the soldiers answer at the top of their voices.

"F**king hell, we’re finally going home!" one of the Ukrainian soldiers exclaims happily.

"Suleiman from Chernihiv", "Baton from Kamianske", "Kharakternyk from Kyiv"… The soldiers are on their way back to Ukraine after their training exercises in the UK.

Next stop: war.

Authors: Anhelina Strashkulych, Yevhen Buderatskyi

Translation: Yelyzaveta Khodatska, Yuliia Kravchenko

Edited by: Teresa Pearce