The White House says Russia and Ukraine have agreed to a ceasefire in the Black Sea, with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy asserting the truce was effective immediately while also accusing Russia of lying about the deal’s terms.

Needless to say, it’s far from clear that United States President Donald Trump’s supposed “Art of the Deal” negotiating skills are enough to broker sustainable peace between Russia and Ukraine given the protagonists’ unwillingness to make concessions and the volatile nature of attempts to broker a peace agreement.

The war waged by Russia has reached the stage where both Russian and Ukrainian officials fear losing face if they make concessions.

Both view their enemy as an existential threat. Russian President Vladimir Putin has argued Russian defeat would spell “the end of the 1,000-year history of the Russian state,” while Zelenskyy says Russia’s protracted assault is an overt existential threat and the absence of U.S. support threatens the very survival of his country.

Both sides have seemed prepared to fight until the bitter end. The involvement of a mediator in the form of the United States, therefore, could potentially change the deadly dynamics of the conflict.

‘Love to beat them’

Trump declares being up to this formidable task. He positions himself as a mediator occupying a middle ground between the protagonists, unlike his predecessor in the Oval Office who supported Ukraine.

In his ghost-written book The Art of the Deal, Trump claimed to enjoy these sorts of challenges:

“In New York real estate… you are dealing with some of the sharpest, toughest, and most vicious people in the world… I happen to love to go up against these guys, and I love to beat them.”

But if mediators, including Trump, are to successfully persuade opposing sides to make a deal, they need to properly understand each side’s motives. To what extent is each side malleable so some common ground can be found? Making a deal always requires compromises and concessions.

Trump is well aware of this, saying recently of any prospective Russia-Ukraine agreement: “You’re going to have to always make compromises. You can’t do any deals without compromises.”

Understanding motivations

David McClelland’s theory of human motivation may be relevant in terms of attempts to broker peace between Ukraine and Russia. The social psychologist argued that three motives — the need for achievement, the need for affiliation and the need for power — explains most human behaviour:

- The need for achievement explains the desire to be productive and get results;

- Concern about establishing, maintaining or restoring a positive relationship with another person or people underpins the need for affiliation;

- The will to dominate, to have an impact on another person or people, is the essence of the need for power.

McClelland predicted that when the need for power significantly exceeds the need for affiliation, conflicts and wars are likely. He viewed a high “power-minus-affiliation” gap as indicative of what he called the “imperial power motive syndrome.”

Read more: Too much power can do very odd things to a leader's head

The metaphor of an empire lies at its origin. The empire’s declared mission is to enlighten, civilize and bring order to its subjects. Leaders with the imperial power motive syndrome show reformist zeal to save others, whether they like it or not.

The social psychologist Robert Hogenraad subsequently adapted McClelland’s theory for computer-assisted content analysis by developing dictionaries of the three needs.

If the words associated with the need for power — control, domination, victory, for example — occur more often in a text, speech or news reports than words associated with the need for affiliation — like love, family, friends — then the speaker has the imperial power motive syndrome.

Hawks vs. doves

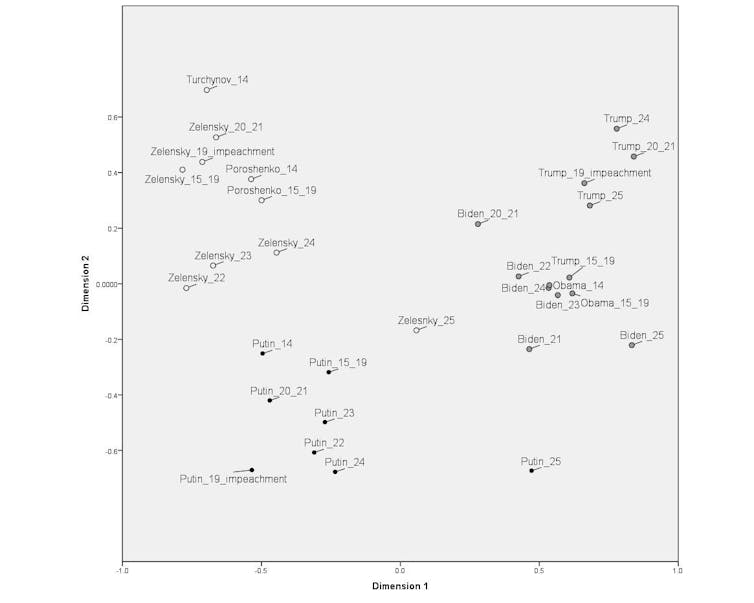

My recently published analysis of war-related speeches delivered by Russian, Ukrainian, American, British and French leaders during the three years of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine gives some clues about the motivations of the parties involved.

Compared with their western counterparts, Putin and Zelenskyy exhibit the strongest imperial power motive syndrome and are “hawks.” Their need for power, as expressed through their public speeches, significantly exceeds their need for affiliation. Trump, however, appears similar to that of his arch-rival, former president Joe Biden. Both are closer to the “dovish” end of the scale.

The preliminary outcomes of talks on a potential ceasefire reveal the challenges faced by mediators.

First, the talks being held in Saudi Arabia were bilateral, with American officials meeting separately with Russian and Ukrainian delegations, as opposed to trilteral.

Second, no joint statement followed the talks, although it was widely expected.

Third, the White House issued two separate statements, one on talks with Ukraine’s representatives and the other on discussions with Russia’s representatives.

The Ukraine statement includes the commitment to continue the exchange of prisoners of war, the release of civilian detainees and the return of forcibly transferred Ukrainian children, whereas the statement on the talks with Russia does not mention any of this.

This is despite the fact that the International Criminal Court has accused Putin of committing war crimes via the unlawful deportation of children.

Trump’s antipathy toward Zelenskyy

The prospects of a peace agreement is further complicated by the history of Trump’s attempts to broker deals in Ukraine.

The war in Ukraine actually began in 2014 with the annexation of Crimea and a proxy war in Donbas. Trump was elected president two years later.

His discourse about Ukraine did not differ significantly from Obama’s and Biden’s until his first impeachment in 2020 for soliciting “the interference of a foreign government, Ukraine, to benefit his re-election.”

His call to Zelenskyy in July 2019 triggered the impeachment. He pushed for two investigations aimed at helping his re-election bid — one into Hunter Biden’s business dealings in Ukraine and another into the hack of Democratic National Committee servers in 2016 — in exchange for releasing about $400 million of military assistance already approved by Congress and inviting Zelenskyy to the White House at that time.

During and after the first impeachment, Trump’s language on Ukraine significantly diverged from Obama’s and Biden’s. He began using words like “corruption,” “lies” and “hoax” in relation to Ukraine.

Moving forward

All this suggests that Trump’s first impeachment has had a lasting impact on his perception of Ukraine and its leader.

And so in addition to dealing with two protagonists who are unwilling to make concessions, Trump as a mediator faces challenges related to his past.

One protagonist, Zelenskyy, may remind him of one of the darkest moments in his political career — his first impeachment. This fact should be kept in mind when trying to make sense of the treatment received by Zelenskyy during his most recent visit to the White House and Trump’s references to him as a “dictator.”

To truly succeed in mediation, Trump must move forward, leaving biases and prejudices related to Ukraine and its leader in the past. But can he?